What is Science?

Mountain Connection, September 12, 2022

By Jed Donnel, Upper School English Faculty

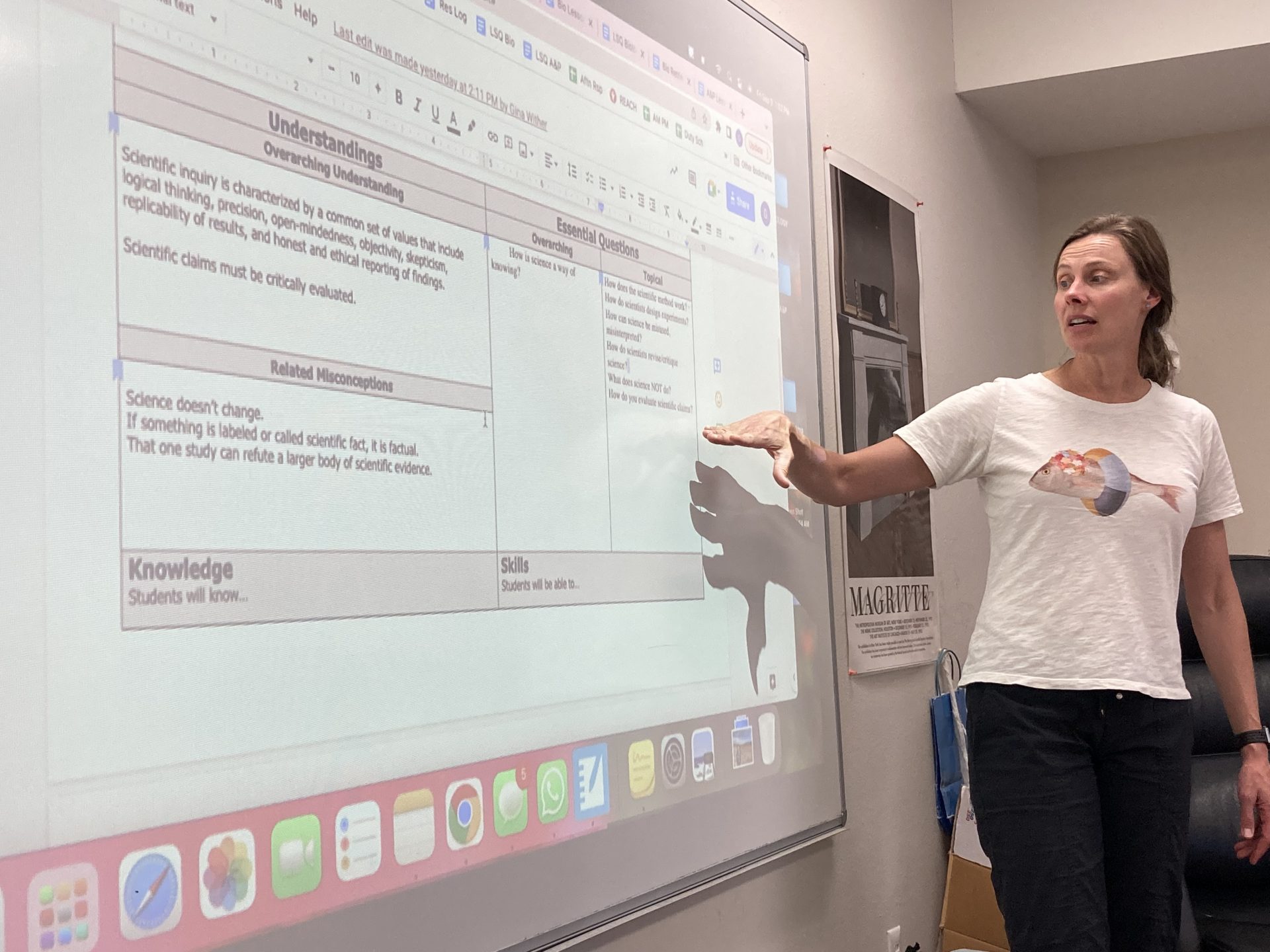

Last week, Gina’s 9th graders embarked on a two-fold process of discovery based within the continual association of two questions: ‘what is science?’, and ‘what is Science class?’ For the first, they are coming to terms with the scientific process, which helps to explain the methods by which the discipline continuously strives to solve the riddles of the universe (no small task). For the second, they are experiencing and experimenting with all the normal nervous and quirky wonderings of the first weeks of 9th grade, including how to make sense of the specific idiosyncrasies of their different teachers. To assist them in both capacities, Gina has merged the two processes by using the class, itself, as an analogue for the scientific process. Very ‘meta’. What does that mean? Well, the scientific process rests on the following modes: question, research, formulate hypothesis, experiment, and publish. By thinking about and articulating how those same steps apply to Science class, too, the students are bringing tangible, relatable steps regarding themselves to the abstract idea of imagining scientists in the field. For instance, last Friday’s class began with a ‘low stakes quiz’ in reaction to a reading on the scientific process, and Gina made clear that the results would formulate a round of data collection (students’ results in comprehending the reading) that would help her to modify her own experiments (lesson plans). The four questions were based in comprehension of the reading assignment, and then students added a self-evaluation by applying a short key per answer: star for “I certainly knew that”, and ? for “maybe I knew; not sure.” The results, therefore, became two different sets of data – what students actually knew and what they thought they knew – and each can now be measured and cross referenced to assess how well they prepared. Moreover, the students had been pre-assigned to two different control groups: both read the same assignment, but one was merely given the reading, whereas the other was also given time to write, reflect, and ask clarifying questions within a discussion prior to the quiz. Therefore, the different data sets for each group also provide evidence for which study methods resulted in higher comprehension.

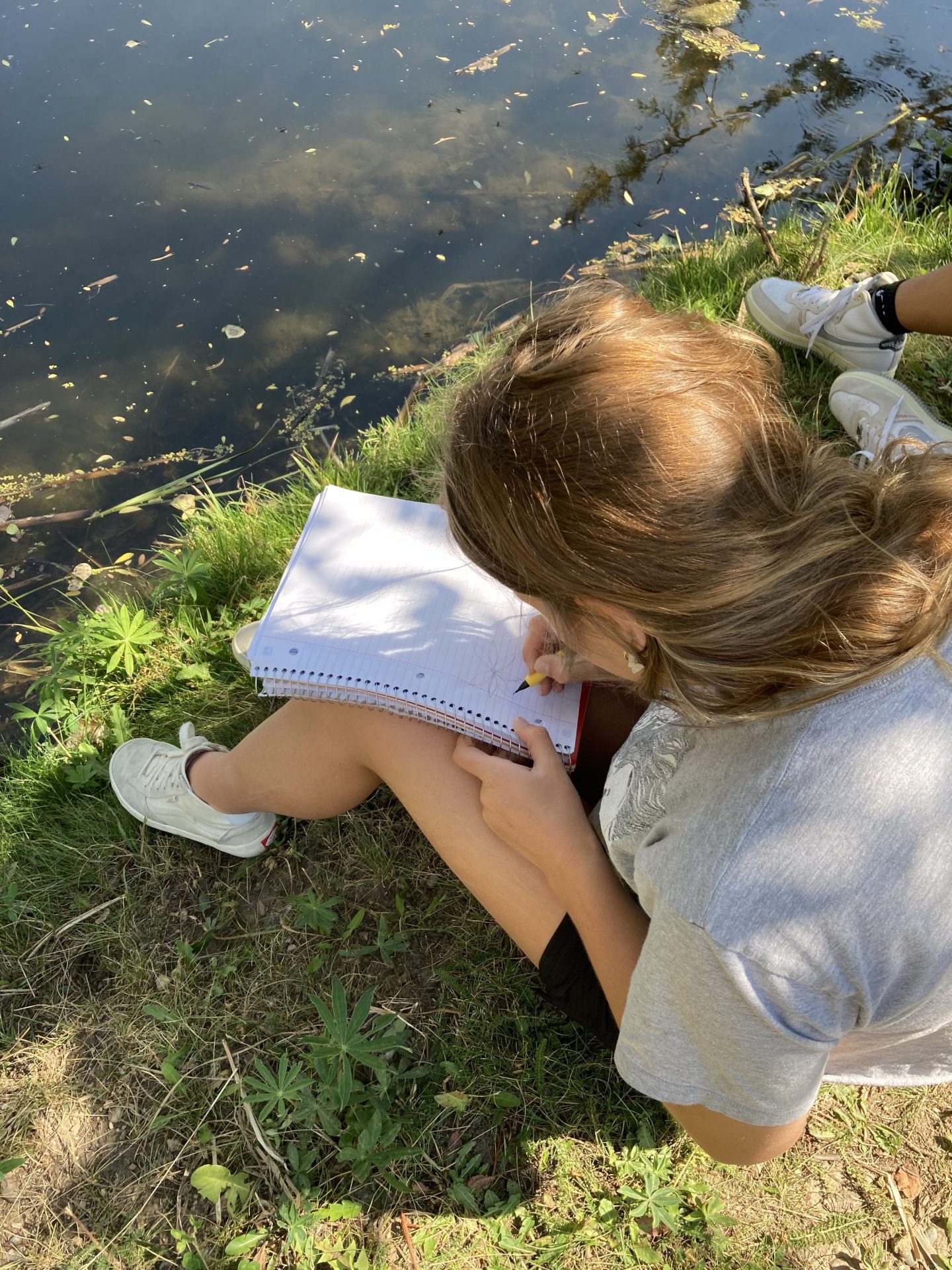

Gina followed the quiz with a series of metacognitive steps by which students expressed the differences they had experienced in process and outcome. They discussed answers to prompts such as, “Let’s talk about what we just did” and completed memory-enhancement practices such as ‘brain dump’ and ‘kinesthetic association’ that Gina had picked up as experimental practices from her faculty summer reading. Together – teacher and students — are all figuring out the modes that work best for them as a group and contemplating how such processes apply to, and speak about, the time-honored methods of collecting and assessing scientific data in the field. As a logical extension, therefore, they culminated the class period by heading into the field to collect their own data. One of our new Teaching Residents, Hannah (herself experimenting with the various processes of teaching), took over in dividing the students into four groups around the pond to investigate distinct plant life: cat tail, aspen, willow, and lupin. Hannah likewise provided questions by which the students focused their empirical data. She asked, “What specific characteristics do you notice about your plant?” In attempting to produce a detailed drawing, the students trained their eyes on intricate detail. In the process, they formed their own questions. “What are those spots on the leaves of the aspens? Why does the willow appear to be a collection of different stems lumped in the same area? Why is the cat tail pointy on top?” Since their questions originate in their own observed data, the next step (which they’ll begin this week) involves devising a hypothesis and accompanying experiment to arrive at their own data sets. By imbedding the purposes of the subject matter within the content, Gina will be able to assess not only the steps of the scientific method that each student understands but the degree to which they are able to apply their learning to the course of their own discoveries.

Curating an Authentic Wilderness Menu

To celebrate the end of a novel studies unit about characters who had to survive in the wilderness, our class prepared a feast of foods. They chose foods that shadowed what the characters might have eaten. Students then shared these foods and described how they connected to their novels with parents and grandparents.

Unlocking Potential: How smartphone-free schools boost academic performance and intellectual growth?

The no-smartphone policy is guided by the school's core principles, which state that "our students learn the power of connectedness through their relationships within the school community and beyond." Steamboat Mountain School is not the first institution to implement this type of policy

Unraveling the Epic: Students Dive into Beowulf

In preparation for their spring production, middle school students have been studying the heroic epic poem, Beowulf. Beowulf is a story of a Scandinavian hero, his support of the Danes through the destruction of monsters, and his inevitable rise to become king of the Geats. Beowulf is considered one of the earliest Anglo-Saxon epics.

A Student Odyssey Through 'One Night in Bangkok

The video has everything, too: quick cuts, dance routines, strange 1980s-era politics (possibly), a watering can, random masks, and a unicorn hat. We landed on the classic one-hit wonder by Murray Head on day one, after sampling an array of other 80s videos.

Capturing Life's Vibrancy: Pia Ostrognai's Journey through Street Photography and Photojournalism | Scholastic Art & Writing Awards Success

Pia Ostrognai, a student from the class of 2025, received recognition at Colorado's Scholastic Art & Writing Awards for her outstanding work in numerous photographs. This prestigious program, catering to students in grades 7-12, stands as the nation's longest-running platform for teens in the arts.

What is non fiction to a kindergartener?

What is the concept of Non-fiction to a kindergartener? How does a kindergartener begin to understand and explore the intricacies of the real world that surrounds them? Enter the world of The Blue Penguins, our vibrant Kindergarten class that has delved into the fascinating mysteries of the ocean!

SMS and The Cycle Effect

The Cycle Effect, a statewide organization dedicated to providing opportunities for young women in the county to build confidence and self-advocacy through mountain biking. Founded in 2011 by Tam and Brett Donelson, The Cycle Effect works with girls in Routt, Summit, Mesa, and Eagle counties, with a specific focus on serving 70% of participants identifying as Latina and/or Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC). Their mission involves removing financial barriers while supporting the social-emotional well-being of participants.

8th Grade Winter Skills

Winter Skills is always a test, but not in the sense you might think. When I first started at Emerald Mountain School students felt obliged to share the hype of this treasured tradition often and early. By all-school camp trip in August, I had learned of their cold weather fortitude, fire-starting abilities, and enduring isolation in the backcountry. Now, with the hindsight of plenty of Winter Skills trips behind me, I’ve bore witness to all these skills developed and executed over the years. Despite the importance of building backcountry safety and acumen in our middle schoolers, I feel it misses the full value of the trip in my opinion. What I’ve come to cherish most about the trip is the coalescing of each unique team of students and how it always seems to push them to consider how they want their legacy at the Emerald Campus to be remembered.

The Swish

Last Monday afternoon, two storied franchises squared off in the latest, epic installment of their ongoing rivalry for the title of “best organized basketball team south of the resort and including but not east of County Rd 36.” That’s right, Faculty vs. Students. My schedule being occasionally amenable to such undertaking this year, I joined the faculty squad with the lofty expectation to sustain our unprecedented winning streak across all years and every individual contest (at least per the anecdotal evidence I’ve received).

Chocolate

For the last month in 3rd grade, students have been learning about chocolate around the globe! While the topic is pretty sweet, the purpose behind this unit and subsequent PBL project is to learn about geography and countries by teaching our students about continents, landforms, and trade via the lens of chocolate.

Syrian Tea with the 6th Grade

In 6th grade, we have been exploring the elements of demography and how unstable politics can lead to surges in migration. The students narrowed that lens particularly on refugees from the Middle East and their journeys to find safety in Europe. We have just finished reading "Nowhere Boy," a novel about a boy from Syria who has become a refugee, which

Robots in the Classroom

Our teachers are on a mission to foster adaptive thinking skills among our 3rd and 4th-grade students, utilizing modern technology, particularly the Fable Robot System. This system provides modular, durable, and scalable learning tools that captivate and engage students. The robots are operated through software, enabling students to construct block code and achieve interactive results. As students gain experience they naturally transition to coding in Python.

Creating Inclusive Learning Spaces: A Spotlight on Emma Terwilliger, SMS Learning Support Coordinator

“I was drawn to working in learning support because I want to create inclusive educational spaces where students feel supported in learning. I believe that in order for these spaces to be possible, all students need to be able to show up in the classroom as their full and unapologetic selves and be valued and supported for who they are.”

Spirit Week

The first of several Spirit Weeks—monthly, perhaps? Sure, why not? — took place last week to much fanfare. As the leaves change, so too does many a student perspective amid realizations of materializing due dates, actual grades, details of major assessments, and even the nearness of the midterm for the first trimester (already!).

Identity through 'mirrors' and 'windows'

Mirror moments involve empathy– how do the character’s feelings and actions remind you of something you have experienced? Window moments encourage sympathy and compassion– how does the character’s experience teach you something new that you had not thought of before? The key to this exploration is authenticity, as students are encouraged answer these questions honestly, rather than arriving at pre-loaded responses.

Watersheds and macro-invertebrates in Gothic, CO

During our hike to Judd Falls, we encountered a variety of spruce and fir trees, pausing occasionally to measure their crown size, diameter at breast height (which we affectionately referred to as "Genevieve height" since it matched one of our team members perfectly), and the health of their needles, all for RMBL's research database. In the afternoon, we had the privilege of meeting the highly anticipated billy barr (who intentionally spells his name in lowercase, not a typo).

We Love His-tor-y! We Love History!

Joanie’s U.S. History class is high energy. She is upbeat, energetic, and humorous by nature (the sort of glowing attributes that, for me, require the consumption of a couple of cups of coffee to begin to conjure). So, even as they walk into the room, her student know (and enjoy).

Teamwork and Expedition Behavior

Last week marked an exciting kickoff for our first “Friday in the Field," as middle school students gathered to practice expedition behavior (EB). Expedition behavior encompasses a set of essential rules designed to foster group success in the backcountry. Leading the morning's lesson was Sophie Coolidge who emphasized, "We often say that practicing good expedition behavior is akin to treating each member of the group as if it were their birthday."

"Senior Thanks"

As with many traditions in folklore, the origin story of ‘Senior Thanks’ is something of a mystery. Eben notes, “I'd wager it had something to do with Brian, Meg, and a senior prank gone wrong, but I actually don't have a good sense of the history.” As follow-up, Brian states, “Senior pranks moved into ‘Senior Thanks’ about a decade ago

Many Happy Returns

Spring has sprung! The bears are out, the robins are hard at work, and there’s a general vibrancy in the air amid warmer weather and waking flowers (even despite a few recent snows). Perhaps nowhere on campus was the excitement more apparent than around the front office last week as returning GS students were greeted with screaming jubilance on campus.

Laughter as a Tool

I believe in laughter. Laughter brings people together. A silly joke or a funny song can make two people forget about a fight they just had or something upsetting. I was listening to music with someone I had just met a few days ago and hadn't ever really interacted with them yet and a funny song started playing.

SMS Trio Dazzles at Junior Nationals

Multiple SMS students competed around the world last week. Amid the flurries, corkscrews, twists and turns of various venues spanning North America and Europe, they managed a challenging and exciting schedule around their academic responsibilities. Locally, Steamboat was pleased to sponsor the U.S. Junior Freestyle National Championships

What is intersession?

In this, my first year of teaching at the SMS Upper School, the question posed by the title has been on my mind lately. I’ll be teaching Intersession in a few weeks, and I need to know what to expect. In essence, Intersession provides the opportunity for our competitive skiers and riders...

The Biathlon Bug

Coming into the range, I could hear the familiar sounds of my poles piercing the snow and the new and strange noises of rifles firing. It was freezing, and my hands and feet were cold. Large snowflakes were falling, making it incredibly difficult to see. When I found my mat, I struggled

AI In the Classroom

With artificial intelligence all over the news lately, I am reminded of why I value teaching, particularly at a small, independent school. I do not share the various fears regarding A.I. that have apparently plagued many in the education field lately, and especially since the late fall when ChatGPT went live and became, by credible accounts

Community With Meaning

The tone I seek to set is one of trust, playfulness, and engagement. I strive to make students feel seen and respected as individuals, to celebrate with them in their successes, and work with them in their failures.” And while the SMS student calendar can vary widely for different students, whether day, boarding, skier or GS, our collective experience bonds us and characterizes our broader understanding.

Swoosh, thwap, swooth!

Wind, cold, bitter wind cuts across my exposed face. Thwap. I listen for the gates as they hit my shins. The familiar swoosh that my skis make when I turn echoes the wind. Thwap, swoosh, thwap, swoosh. The welcoming sound of people cheering me on as I fly through the final gate and the finish line just beyond it. Then it is all over, the tension, the anxiety, and the adrenaline.

Winter Carnival and SMS

This Friday, February 8th, the 110th Winter Carnival will commence in Steamboat. The event is unique and wonderfully indicative of the magic of the town. Where else on earth would you expect to see organized skijouring events including shovel races, children pulled behind galloping horses through slalom courses and off jumps down the middle of a main street adorned with locally-made snow sculptures, the Soda-Pop Slalom, and of course the Lighted Man, lights parades of SSWSC athletes, ski patrol hurling themselves through a ring of fire and off the HS75 jump, and a magnificent fireworks display?

A Straight A Student: Autonomy

Autonomy, or self-direction, is a critical motivator for humans. While we are all willing to comply with other’s wishes and directions to varying degrees, most humans produce far better when they are given autonomy to make decisions. We should strive to create more opportunities for autonomy for our kids and relinquish control when we don’t need to exercise it.

Who are the Residents?

As the first trio to embark on SMS’s new Teaching Resident program, our three faculty in training have been trailblazers, both in implementing what the program is intended to be, as stemming from its paper-based concepts, and in the ongoing process of experimentation and modification as we figure out on the fly what the job really entails on a day-to-day basis.

Generation U

In July of 2022, two of my friends went to the town of Magale in Uganda, Africa to build a well. They returned with stories that inspired me. Their group was invited into a family’s crowded home and thanked by all of the members of the family. As thanks for the water they brought to their village, the family gave the group a goat and a chicken.

Alumni Highlight: Kaeli Nolte

Kaeli Nolte, SMS class of 2009, can usually be found in Portland, Oregon, where she is the Principal Founder and CEO of Zone Design Group, an architectural firm focused on creating sustainable, avant-garde structures that merge what we commonly think of as distinct ‘exterior’ and ‘interior’ spaces.

The Straight A Student: Altruism

This is the second of a four part series of articles about The Straight A Student. If you missed last week’s article about achievement, you can go back and read it (and many other past posts) here. This week, I would like to continue exploring what makes for strong student connections and success in school by writing about altruism, the second “A.”

On the merits of group coffee consumption

During Winter Break, some divine entity – which either inspired the generosity of a terrestrial benefactor or landed on earth itself, shrouded in the mystic clouds that otherwise grace the peaks of Olympus, and delivered the literal contents of this article – bequeathed to the Upper School faculty an amazing Breville all-purpose, do-it-your-self, coffee-house-esque extravaganza.

Mapping out the College Process

For seniors everywhere – and their parents – the college application process tends to be a daunting experience. Rest assured, in either grouping, that SMS students are in good hands. Our college guidance department (now composed of four adults for seventeen seniors and twenty-one juniors) works as a collaborative group to place the stressful aspects of the process into a realistic perspective. The entire puzzle for applying to college involves two paradoxical extremes: a broad expanse of mysterious, ineffable, and seemingly life-altering decisions, and the logistical minutiae of due dates, word counts, and required steps. In true SMS spirit, each member of the department adds their own personal touch to account for the whole undertaking. The captain of the ship, Gilbo states, “I love helping students figure out how to translate their big-picture dreams into realistic next steps, to identify and broaden their exposure to new places, new options, and new ideas, and then help them to comprehend the detailed work involved in seeing those abstract ideas become tangible.”

Intersection of the Mtn and Emerald Campuses

Grand Opening Today! I am excited to share that Samantha and Andy came down to host the grand opening to our new school building today. All students got to come in for a tour and a treat. Starting today and continuing throughout the week, we will begin rolling out our classes and music lessons in our new space.

Grand Opening

Grand Opening Today! I am excited to share that Samantha and Andy came down to host the grand opening to our new school building today. All students got to come in for a tour and a treat. Starting today and continuing throughout the week, we will begin rolling out our classes and music lessons in our new space.

Authentic Assessment

Paper, bridge design, 3-D model, and presentation: the ingredients for an engaging approach to mathematics. For Emily Spangler’s Applied Math course, students recently completed the sort of project-based assessment that best exemplifies the complex ambition of “authentic assessment.” Rather than the traditional ‘plug-and-chug’ requirements for a standard math test, which is usually a summative assignment meant to demonstrate what a student knows by the end of a unit, authentic assessment includes a much more dynamic and thorough approach.

Winter Wonderment 2023

Winter Wonderment 2023 was a huge success, spanning ski trips to Jackson Hole and Salt Lake City's surrounding resorts, ice climbing in Ouray, sports and arts in Denver, and a backcountry hut trip in Aspen. This coming weekend, Margi and Treania will host students at Trenia's ranch for an immersion into Steamboat's deep farming roots. Click below for pictorial highlights.

Canyons, Canoes, and Cassettes

Last week, I enjoyed my first ‘Desert Week’, a decades-long tradition for Upper School students that breaks from the academic calendar midway through the first trimester to partake in the expanded classroom of the great outdoors. This year, students opted between canoeing, mountain biking, canyoneering, or backpacking excursions, each trip centered around greater Moab, which is some of the most spectacular landscape on earth.

Knowledge and skills through PBL

Project based learning isn’t always the fastest route to learning, but it can lead to the deepest learning. When projects and partnerships succeed, and when they fail, students are gaining insights that they will transfer into future experiences. And to top it off, projects are fun!

2022 Commencement

On Saturday, faculty and staff gathered with families and guests to celebrate Commencement for the 2022 seniors. Head of School, Samantha Coyne Donnel’s speech spoke to the value of the SMS experience of the class of 2022's time at SMS, “Last year Gina Wither shared with me that SMS’ unofficial motto is ‘you’ll thank us later’.

Technological Sustainable Future

The Steamboat Mountain School’s IT Explorations class recently visited Yampa Valley Sustainability Council (YVSC) to recycle electronics. Landfills will not accept electronics due to the possibility of leaking toxic contaminants, sparking fires, or causing other hazardous conditions. Anything that has a battery or plugs in can be recycled at YVSC!

Where is this thing going?

Asking a kindergartener to tell you a story is always an interesting task, one surely filled with adventurous intrigue, but that may also try the patience of even the most hearty of souls. One tends to wonder, ‘Where is this thing going?,’ often including the storyteller, who may not be at all sure until the plot hits an unforeseen roadblock. To assist the design and outcome of such undertaking – while fostering its creative merits – Merrick has recently designed an ingenious unit for the Eagles.