What is "comprehensible input"?

Emerald Connection, December 12, 2021

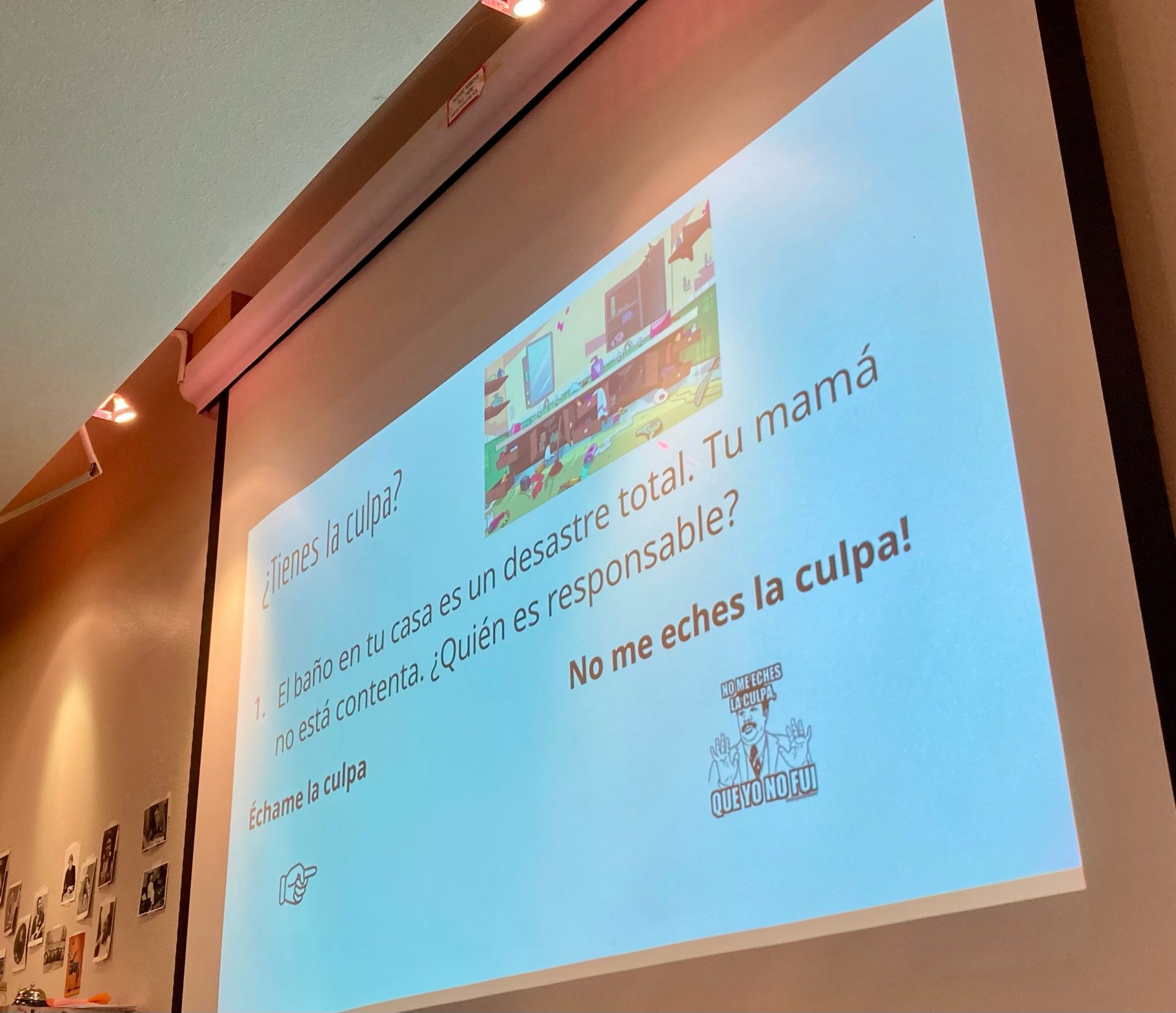

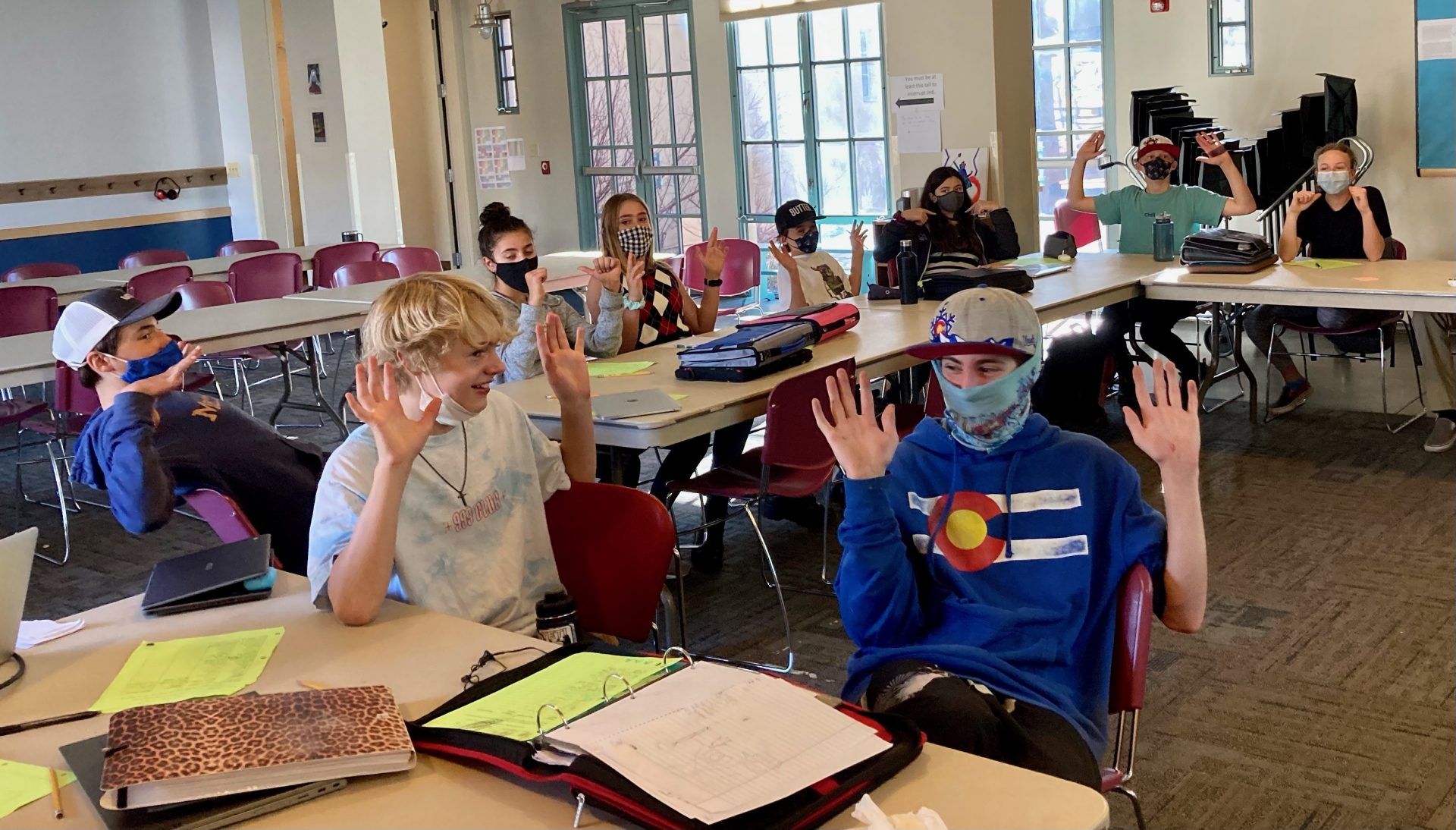

Step into an MS Spanish class these days and you’ll be treated to Andrea’s immersive, engaging methodology. When you do, be prepared to move, to discuss, to laugh, to read, to interact, and to experiment with the subject matter on a personal level. What academics lately call “comprehensible input” or, in relatively older days, “(T)otal (P)hysical (R)esponse and (S)tory-telling,” is far from the traditional rote from days of yore. Instead, in what comes across on any given day as “Spanglish” – part new terminology in Spanish, lots of questions, at least half English so as to understand new context, and lots of conversation – students learn by doing, as they did (and still do) in acquiring their native tongue. Last week, for example, I witnessed a lesson on culpability, for which students were given a couple of options displayed prominently on visuals: “echame la culpa” (put the blame on me) and “no me eches la culpa” (don’t blame me). To warm up, they each wrote scenarios on sticky notes (most in English; some in Spanish) that would merit blame – any blame – and submitted them to Andrea who read each out loud as the students reacted to whether such blame warranted individual guilt. The lesson included lots of body movement and inflection so as to emphasize the two options, while students held up their hands to express their innocence or pointed at themselves and nodded to accept blame. In essence, therefore, the process lent itself to the extensive repetition needed for such comprehension, although (differently than what I endured in middle school) the repetition itself was not the focus. Instead, students all actively experimented with their own gestures and tones of voice (even as sarcastic self-derision) while they practiced the terminology they needed to express themselves. In the process, Andrea seamlessly worked in expressions in Spanish, some that the students had learned before and others they determined on the fly and in context, while the conversation bounced back and forth between teacher and student in and out of the new language. They asked her clarifying questions, both in English and in Spanish, they were given feedback in both languages, and they sustained a high level of energy throughout. Clearly, too, Andrea used past methods as scaffolding for new material, like midway through class when they all stood up, found a new conversation partner in the room, and used emoji patterns on the board (with several new options added that day) to describe their own emotional state in the moment. Andrea walked the room, too, listened as the students expressed their states of being, and added clarification and comedic context to keep the material light-hearted. As the lesson further unfolded into video and other visuals, she buffered more advanced content and expansive diction with good, old-fashioned toilet humor; students debated the relative culpability between dog and owner in reaction to a cartoon depicting two such figures with differing facial expressions standing opposite a puddle of “pipi.” Colloquialisms are certainly a part of language too, after all. And, the low-level context definitely assisted the students’ understanding of high-level material, as they seemed to forget that they were learning something new. Rather, they worked themselves into the joke by using their new knowledge. Such processes are transferable across content, whether literature or cartoon, current events or simple scenarios. Andrea clearly takes a vested interest in who her students are, and they become the primary subjects of the course. Rather than translation, Spanish thereby becomes part of their mode of thought. In consequence, they increasingly move toward fluency by using the language to express themselves as real people.